- Home

- Marie Joseph

Since He Went Away

Since He Went Away Read online

Contents

About the Author

Also by Marie Joseph

Title Page

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Love Is Like That

Copyright

About the Author

Marie Joseph was born in Lancashire and was educated at Blackburn High School for Girls. Before her marriage she was in the Civil Service. She now lives in Middlesex with her husband, a retired chartered engineer, and they have two married daughters and eight grandchildren.

Marie Joseph began her writing career as a short-story writer and she now uses her northern background to enrich her bestselling novels. Down-to-earth characters bring a vivid authenticity to her stories, which are written with both humour and poignancy.

Her novel A Better World Than This won the 1987 Romantic Novelists’ Association Major Award.

Also by Marie Joseph

A Better World Than This

The Clogger’s Child

Emma Sparrow

Footsteps in the Park

The Gemini Girls

A Leaf in the Wind

Lisa Logan

The Listening Silence

Maggie Craig

Passing Strangers

Polly Pilgrim

The Travelling Man

A World Apart

Since He Went Away

Marie Joseph

For Muriel

Prologue

AMY BATTERSBY WAS a well-respected, cheery girl. Everybody liked her and often said they felt better for seeing her. It was obvious she adored her husband Wesley, who was tall, dark and handsome. Like a film star, some said. Like a tailor’s dummy, others muttered.

Amy was quite pretty in a nondescript way, with toffee-brown hair and a neat little figure. She could easily have passed for twenty-seven instead of ten years older. She laughed a lot, but never at other folk’s misfortunes, and if she could be faulted it was that she lived in a fantasy world where everything in the garden was perpetually lovely, where families talked to each other like characters in Little Women.

It was true to say there wasn’t a mean bone in Amy Battersby’s body, yet on the New Year’s Eve following the Abdication in the December of 1936, Wesley went out of their house into the street to bring in the New Year. He carried a cob of coal in his hand, according to northern tradition. Amy closed the door behind him quite happily.

At the hour of midnight clocks chimed and guns boomed, but there was no knock on the door, no smiling Wesley bringing in the New Year with kisses all round and a chorus of ‘Auld Lang Syne’.

Wesley had disappeared. Vanished. Gone. Leaving a slab of coal on the doorstep and the smell of his last Wills’s Capstan cigarette lingering in the vestibule.

1

AMY ALWAYS HAD Wesley’s parents and her own mother round on New Year’s Eve for a bite to eat and a bit of a sing-song round the piano. Wesley, who possessed a rather fine light baritone voice, was a member of the local operatic society, and had played the Red Shadow more times than most folks in the town had had hot dinners.

Gladys Renshawe, Amy’s mother, wasn’t much of a mixer, but she wouldn’t have missed the little get-together for all the tea in China. She considered the Battersbys to be very much her social superiors, and thought it a privilege to be there to see in the New Year with them.

Phyllis and Edgar Battersby lived in a red-brick detached house called The Cedars, up by the Corporation Park. They had a telephone and a car, and went all the way down to Bournemouth every year for their holidays, which set them well apart from the likes of Gladys, whose husband, before he died, had been a warehouseman in a local cotton mill.

Gladys was very proud of the way her daughter had gone up in the world when she married into the Battersby family. Edgar, who called himself a cigar and tobacco merchant, owned no less than three shops, one in Blackburn, one in Darwen and another in Preston, catering, as he said himself, only for the better class of customer.

Yes, Amy had done well for herself, but her mother couldn’t help wishing that she would brighten herself up a bit. Perhaps wear something that picked out the colour of her blue eyes instead of that brown dress with the cream organdie collar and cuffs. It only needed a frilly pinny and Amy could have been taken for a waitress in a tea shop. Gladys felt like ordering a toasted teacake and a pot of tea for one every time she looked at her.

Phyllis Battersby never wore brown, except for her furs, of course. She wondered why her daughter-in-law thought the colour suited her. There was no accounting for tastes.

Her husband Edgar wondered how soon they could get away. Wesley was obviously in one of his moods, not that his mother would notice. She thought the sun shone out of his backside, always had. Edgar narrowed his eyes and hid a small belch behind a hand. He wondered who Wesley took after with his flashy dark good looks and his musical leanings. His hair was so black you would think there was a touch of the tarbrush in him; though how could there be when there’d been Lancashire Battersbys for generations – right back to Cromwell and Marston Moor.

It was very hot in the small living room with the flames from the fire leaping up the chimney back. Edgar watched a fleece of soot hang quivering. He would have to go down the yard again to the lavatory for the third time. The salmon sandwiches, sherry trifle and rich fruit cake were playing his stomach up, and when he stood up and saw his face all lopsided in the scalloped mirror over the fireplace, he almost recoiled. Was he really as ruddy-complexioned as that?

‘Best be quick, Mr Battersby,’ Amy’s mother called out as he tried to leave the room unnoticed. ‘Only five minutes to go before your Wesley goes outside to fetch the New Year in.’

Amy saw the way her husband’s lip curled. She’d been trying to jolly him out of his black mood all evening, but he wasn’t having any. He’d played the piano and sung ‘One Alone’, then for some reason started to play cross-hands, thumping a foot down so hard on the loud pedal that a photograph of him dressed as the Red Shadow jumped at least six inches in the air.

‘Come on, love,’ she said, half pushing him down the lobby and through the front door. ‘You’ll have to go now if you want to be outside before midnight.’

Back from his trip down the yard Edgar advanced on the glasses of ginger wine set out ready on a tray. ‘Are your glasses charged?’ he boomed, being a big Mason and knowing the right phraseology.

From the wireless Big Ben chimed the last seconds of the old year away. Amy started for the door to let Wesley in.

‘He’s not knocked yet,’ her mother shouted after her. ‘Wait till he’s knocked.’

‘Come on, lad.’ Edgar needed to sit down. He’d got shocking indigestion, and a pain underneath his right ribs, which had troubled him a lot lately. He considered the ginger wine in his glass to be a decidedly funny colour. Why they all had to pretend to be teetotal he had never understood and never would. Wesley could sup a reservoir and still sing God Save the King backwards, and his mother was partial to a drop or two of sherry – a drop or three at times.

Phyllis was smiling now. ‘Wesley’s playing one of his little jokes on us,’ she was saying, neat as a doll-in-a-box in her mauve knitted two-piece. She put up a hand to her grey hair, fussing with her marcel wave. ‘He doesn’t usually miss his cue.’

‘Come on, lad,’ Edgar said again. ‘It’s coming down like stair-rods outsid

e. What’s he playing at?’

Amy put her glass down on the table and said she’d go and see.

When she opened the door Wesley wasn’t there. The long street was deserted, its pavements black-wet and shiny from the falling rain. All the other husbands and fathers had gone inside to kiss their wives and mothers and sing ‘Auld Lang Syne’. She could see one lot across the street through their front window, jumping about and acting daft, wearing paper hats and throwing coloured streamers about the room.

She shivered, rubbed the tops of her arms, moved from the doorstep and felt the rain on her head. The houses either side of her were in darkness, their occupants obviously gone to bed. Amy hesitated at the door on her left.

Last year Wesley had invited Dora Ellis to join their little party, but it hadn’t been a good idea. How could it have worked when Dora cleaned part time for Phyllis, doing her rough for sixpence an hour? The atmosphere had been filled with embarrassment, what with Dora trying to act posh, Phyllis ignoring her and Edgar overdoing the mateyness. Wesley had thought it a scream to see his mother struggling to treat her char as her social equal.

This year Dora had gone to bed alone. Amy looked up and saw a light was on in the front bedroom, so there would be no point in knocking to ask if Dora had seen Wesley.

‘Wesley?’ Amy turned and walked back to the doorway. ‘Wesley?’ Feeling foolish, she called his name again.

The Battersby Rover saloon car was parked at the kerb. Amy walked over to it and peered inside. Wesley was a great one for practical jokes. As long as they weren’t played on him, Amy muttered to herself, angry now.

‘Wesley?’ Her voice was louder this time.

Maybe he was hiding round the corner, listening to her calling his name and laughing. He’d been in a strange mood all evening.

‘Wesley?’

Amy knew that he wouldn’t be round the corner, hiding from her. That was a childish game, not his style at all. Besides, he hated getting wet, hated discomfort of any kind. He’d told her once, a long time ago, that he had an umbrella with him out in France during the war.

‘Wesley?’ She could hear the panic in her voice. ‘I’m getting wet through.’

A street lamp flickered and went out, and a man loomed up in front of her as suddenly as if he’d popped out of a hole. Amy gave a small scream and backed away, a hand to her throat.

‘Mrs Battersby! It’s only me – Bernard Dale. I didn’t mean to frighten you . . .’

Amy wished her neighbour from further along the street would just keep on walking and go inside his own house. Beneath the brim of his trilby his thin face looked shadowed and sinister, threatening almost, though Wesley had always said Bernard Dale was a pansy.

‘A happy New Year, Mrs Battersby!’

Just as though it was three o’clock on a fine afternoon and Amy was wearing her hat and coat, he raised his trilby and walked on, his rubber-soled shoes silent on the shiny pavement. Not a word about what was she doing out there in the dark and the pouring rain, running about like a wild woman calling her husband’s name.

‘And to you, Mr Dale!’ Amy shouted after him, waiting till she heard him go inside his own house and close the front door before she called out again.

‘Wesley? Stop playing silly beggars. They’re waiting for you an’ I’m getting wet through!’

Bernard Dale had never liked Wesley Battersby. Everything about him was too much. His hair was too black, the waves in it too deep, his glance too bold, his smile too flash. Besides which, he wore a camelhair coat swathed round him like a dressing gown, and suede shoes. Bernard took off his trilby, shook the raindrops from it and carried it through into the living room. He put his raincoat on a hanger and hung it on the picture rail to dry. A sluggish fire, needing no more than a touch of a poker to bring it to life, sulked in the grate. The room was as tidy as if set out for visitors.

A solitary man, an orderly man, Bernard liked living alone. He knew some considered him to be something of an old woman, set in his ways, but he wasn’t going to lose any sleep over that. He accepted, too, that coming from London marked him down as a foreigner in this East Lancashire town, and although he could never get used to what he saw as the overfamiliarity of some of his neighbours, their open-hearted kindness and friendliness never ceased to amaze him. Take this street for instance. Let someone fall ill and it was as though a switch had been clicked on. Basins of hot food passed over backyard walls, errands run, bottles of tonic fetched from the chemist. Two years ago when he’d had flu he’d had at least three offers to rub his chest with goose grease and camphorated oil.

Bernard sat down in his fireside chair, leaned his head back and closed his eyes. It had been a good evening with friends of like minds, listening to gramophone records. Inside his head the music still soared. Debussy never failed him. He waved a finger in time. In a moment he would wind up the clock on the mantelpiece, take off his shoes, leaving them there on the rug with their laces spread, and go up to bed.

He wished to God he hadn’t seen Wesley Battersby walking quickly down Balaclava Street carrying a suitcase; wished to God he hadn’t heard Wesley’s wife calling her husband’s name with blind panic in her voice. Even in the darkness it had been possible to glimpse the fear in her eyes and to sense her terrible anxiety, and now he was implicated, and that was the last thing he wanted to be.

Why hadn’t he told her what he’d seen? He half rose from his chair then sat down again, knowing full well why he’d kept quiet.

Telling would be construed as kindness, not interference, because all his neighbours interfered. Bernard’s fingers beat a tattoo on the wooden arms of his chair. And kindness could rebound. Oh, dear God, how it could rebound. No one knew that better than he. Show sympathy to someone who needed it badly and they latched on. Fast.

If he went to bed now he would never sleep. For all he knew that bonny lass could still be outside searching for her husband, while he . . . Battersby had been walking so quickly, with his head down, was it possible that he could have made a mistake? Bernard picked up a book from the wine table set by his chair and took out a leather-thonged marker. It had been Battersby all right.

By now Amy was past caring that she was shouting aloud in the street, acting common, as her mother would say. Any minute now and doors would open, heads bob out to see what was going on. She was wet, cold and blazing mad, though anger didn’t come easily to Amy Battersby. On the rare occasions when she had lost her temper Wesley had laughed so much she had ended up laughing with him.

Slowly she turned and walked back to the house, hearing the rainwater flowing along the gutter, gurgling like a mountain stream.

‘What’s going on?’ Amy almost collided with her mother shooting out of the door as if she’d been pinged from a catapult. ‘You’re like a drowned rat.’ Gladys shook her daughter’s arm. ‘Where’s Wesley?’

Phyllis came out, holding an umbrella over her marcel wave, keeping her voice low in case the neighbours heard.

‘Where’s Wesley? You’re like a drowned rat, Amy. I think we ought to go inside.’

In single file they went into the house, three anxious women, needing to tell the older Mr Battersby that Wesley seemed to have disappeared. Sure that he would come up with the answer.

Edgar was as red as a beetroot, having managed in the last few minutes to swig at least half the whisky in the silver flask he carried around in his inside pocket. For medicinal purposes, he told himself.

‘You’re very red, Father,’ Phyllis told him in her high, haughty voice.

‘Boozer’s flush,’ Gladys sniffed, smelling the drink on him right away.

‘Wesley’s playing one of his little jokes on us,’ Phyllis said when Edgar failed to come up with anything worth while.

‘I don’t think it’s all that funny,’ Amy said, steaming away in front of the roaring fire.

‘He’ll come in through the door when he thinks we’ve worried enough.’ Phyllis smiled.

‘I cal

l that cruel, not funny.’

Gladys was shocked to hear her daughter speak like that to Wesley’s mother. Amy had gone to sit on the piano stool now, with her damp skirt rucked up, showing her knees.

‘Sit decent,’ Gladys told her, averting her eyes from the sight of her daughter with her hair hanging over her face in wet ropes and her lipstick all chewed off.

‘He didn’t look well to me,’ Phyllis suddenly said. ‘He didn’t look well over Christmas.’

‘I’ll go outside and see if I can find him.’ Edgar prised himself up from the settee, patted his pocket to make sure the flask was still there and trod with careful tread down the lobby.

‘I’ll go after him,’ Amy said in a distracted way. ‘He’s not fit to be out in the rain.’

‘An’ you’ll be fit for nothing if you don’t go upstairs and get those wet things off.’ Gladys turned to Phyllis. ‘Wesley’s not the type to do away with himself,’ she comforted, oblivious to the look of blank amazement on Mrs Battersby’s face. ‘I’ll go through and put the kettle on.’

Phyllis would have followed Amy upstairs if breeding hadn’t indicated that she sat still where she was, discreet as a mother-in-law should always be. She sat on the settee, apparently withdrawn and unconcerned, hearing the gas burner pop in the kitchen as Amy’s dreadful mother put the kettle on. What on earth had she meant about Wesley not being the type to do away with himself? Phyllis shivered in spite of the overwhelming heat from the fire.

Wesley wasn’t in any trouble, was he? Edgar had said something about the turnover at the Preston shop not being up to expectations. Edgar had spared no expense in the fittings, had taken on a second assistant, and only the week before Christmas he’d congratulated Wesley on a most tasteful window display of every conceivable type of pocket requisites for smokers. No one could dress a window quite like Wesley. It was the artistic side in him coming out, the talented side that had been nipped in the bud by that dreadful war and his enforced marriage to a girl who had done nothing to help him express himself. Encouraged, Wesley could have stormed the West End stage down in London. Sung on the wireless. Painted a masterpiece.

The Clogger s Child

The Clogger s Child Gemini Girls

Gemini Girls Polly Pilgrim

Polly Pilgrim Emma Sparrow

Emma Sparrow A Better World than This

A Better World than This The Listening Silence

The Listening Silence Maggie Craig

Maggie Craig Since He Went Away

Since He Went Away Lisa Logan

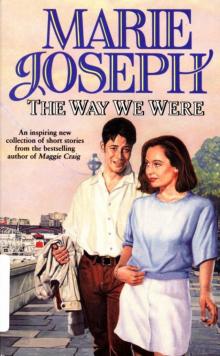

Lisa Logan The Way We Were

The Way We Were The Travelling Man

The Travelling Man Footsteps in the Park

Footsteps in the Park