- Home

- Marie Joseph

Footsteps in the Park Page 2

Footsteps in the Park Read online

Page 2

‘Hard times,’ Ethel said sadly, standing up and showering crumbs on to the carpet. ‘Well, I’d best be off. Our Beryl has a piano lesson at five, and I like to be there. He seems a nice enough young man, but you never know. It’s the quiet ones one has to keep one’s eye on.’

‘That’s true.’

Phyllis tried not to smile as she agreed through a fleeting vision of her niece Beryl, sitting on the piano stool in the hideously furnished lounge of Tall Trees, her sister’s house. Beryl, her ample bottom overflowing the stool, her podgy hands moving laboriously up and down the piano keys, her lank brown hair escaping from its tortoise-shell slide and falling round her plump cheeks. All this whilst her music teacher, the young assistant organist from St. Hilda’s Church, struggled with his rising passion.

‘No, you can’t be too careful,’ she said, going with her sister into the hall, and handing her a grey flecked tweed coat from the tall cupboard with hand-carving down its panels.

‘Who would be a mother?’ Ethel asked as she walked down the drive with her feet at a quarter to three.

‘Who indeed?’ said Phyllis, closing the vestibule door with a bang so that its red glass panels shivered in protest. A couple of hours of Ethel was quite long enough these days. She’d have to talk to Dorothy about the boy from down Inkerman Street. Perhaps suggest a little musical evening with records on the gramophone, or a light supper with that nice young crowd from the tennis club. She might even get her to invite the Armstrong boy so that she could see him set against boys of her own class. She picked up the tea-tray and carried it through into the kitchen.

Mrs Wilkinson, small, and so thin that her body moved skeleton-like beneath the cross-over pinafore she wore, was taking a satisfied peep at the hot-pot simmering slowly on the middle shelf of the gas oven. Her hair, which should have been grey, was a strange prune colour, due to the cold tea which she combed through it every day, and her bird-bright eyes glittered behind the whirlpool lenses of her spectacles.

‘Coming on nicely, Mrs Bolton,’ she said. ‘I’ve turned it down as low as it will go; it’s the only way to cook hot-pot. Long and low. Same with rice pudding. Sure you wouldn’t like me to put one in? Seems a waste of a shelf.’

‘Cheese and fruit,’ Phyllis said firmly. ‘Mr Tomlin’s coming tonight, then he’s taking Margaret to the cinema. We mustn’t make it too heavy a meal.’

She used to say pictures before he came up here, and before she started trying to talk London-posh like he does, Mrs Wilkinson thought, then aloud she said: ‘I bet Mr Tomlin’s never tasted hot-pot like this in all his natural. They don’t know how to cook, Londoners don’t. Cucumber sandwiches is all they know about, and he looks as if he could do with a lining on his stomach. If you don’t mind me saying so, Mrs Bolton.’

Phyllis wrinkled her nose appreciatively, the conversation with her sister having made her temporarily mindful of her help’s undoubted qualities. She leaned forward, a string of amber beads swinging outwards from her chest, noticing the way the potatoes were already taking on the required brown crispness whilst, beneath them, the neck-end chops and the mushrooms cooked themselves into a succulent simmering mash of goodness.

‘Mr Tomlin will leave his usual compliments for the chef,’ she said with a smile, ‘the way he always does when he eats here.’

Mrs Wilkinson beamed, showing a flash of sparkling white false teeth, and a glimpse of artificial gum the shade of a ripe orange.

‘That Mrs Greenhalgh, who works for your sister, thinks she’s it. Just because her husband’s a butter-slapper at the Maypole. And that’s all he is, even though he does try to make out that he’s the manager. What he brings home in that case he carries is nobody’s business, but live and let live, that’s what I always say, and always have said.’

She was astute enough to know that Mrs Bolton was shoving up with her, but why should she bother? As long as her pound a week was forthcoming every Friday afternoon, there was no need for her to go moithering herself. It was a nice enough job, with no scrubbing apart from the lino in the kitchen and bathroom, and no windows to clean on account of Philips, the handyman and chauffeur, seeing to them.

And there were plenty of perks. It wasn’t for nothing she carried her cross-over pinafore and fur-trimmed bedroom slippers up the hill to Appleroyd every morning bar Sundays in an empty basket. Twelve years she’d worked for Mrs Bolton now, and hardly a day when she didn’t walk back down the hill with a little something in the basket. It might be merely one of Mr Bolton’s shirts with slight fray to the cuffs, or it might be a bag of windfalls from the back garden, or even one of her ladyship’s cast-off nighties. She always referred to Mrs Bolton as ‘her ladyship’ when she talked about her to her husband Ned, a porter on the railway.

‘What’s ’er ladyship come up with today?’ he’d ask, having a look in the basket for himself. ‘No wonder the country’s in the mess it’s in when some folks can afford to give good stuff like this away. Better watch yourself if you put that nightie on tonight, lass. See you in that, and I won’t be responsible.’

Then he’d twiddle his non-existent moustache and slap his wife on her non-existent behind. A proper caution Ned was, as she was always telling Mrs Bolton.

They had a comfortable relationship as long as she was careful not to overdo the familiarity. Mrs Bolton liked to hear a bit of gossip, in spite of her prim and proper swanky ways, and Mrs Wilkinson had genuinely felt she was doing her employer a good turn when she’d told her about the way Dorothy walked home from school hand in hand with Stanley Armstrong out of Inkerman Street. You couldn’t be too careful with girls, and she should know, with both her daughters having to be married. And what went on in the pavilion overlooking the Garden of Remembrance between the High School girls and the Grammar School boys would make your hair curl, even if it was as straight as a drink of water.

‘Not that it’s any of my business of course,’ she’d said, down on her knees in front of the wide tiled fireplace in the lounge, newspapers spread all around her as she cleaned the fire-irons and the brass ornaments off the mantelpiece.

She’d dipped a piece of an old vest recently worn by Mr Bolton into the Brasso. ‘The Armstrongs are a clean-living family from what I hear, and it must have been hard going for her since her husband was taken two years back. He worked at the Gas Works, and some say it were the smell what got on his chest.’

Phyllis had tried hard to look as if she thought this possibility was likely. She wanted to find out as much as she could without actually asking questions, but she did wish Mrs Wilkinson would go easy on the Brasso. ‘The more you put on the more you will have to rub off,’ she had once said mildly, only to have to suffer two days of injured silence as Mrs Wilkinson sulked around the house, sighing into her mid-morning pot of tea. So, despising herself for her weakness, Phyllis merely averted her eyes.

Mrs Wilkinson had then told how poor Mrs Armstrong was forced to take in washing.

‘And how she manages with just a living-room with a tiny back scullery leading off it, I don’t rightly know. A friend told me that the poor soul has the rollers on her mangle so tight that she’s in constant pain with straining over the wheel. With half her insides hanging out I shouldn’t wonder.’ She reached over for the three brass monkeys in their hear, speak, and see no evil attitudes. ‘Their Stanley takes the washing out for her after he finishes school, so it shows he’s not got above himself even though he does go to the Grammar School. He’s going to the university, you know.’

‘A state scholarship,’ Phyllis said in some desperation.

Mrs Wilkinson breathed hard on the trio of monkeys. ‘All found I believe through a grant or trust or summat. There’s no doubt about him being clever, no doubt at all. I’ve heard his mother goes on about him as if he might be Prime Minister some day.’

‘Socialist, of course,’ Phyllis had said bitterly.

Two

WHEN DOROTHY CAME in she called out to her mother, then ran straight u

pstairs to change out of the despised school uniform and to have a good think about Stanley and the way he had looked when he’d told her about his sister.

She couldn’t take it seriously somehow. Girls who went missing from home were headlines in newspapers, not girls one knew, and although she had seen Ruby Armstrong in the distance once or twice down at the mill, her impression had been that the girl possessed Stanley’s quiet dignity. Certainly not the type to deliberately frighten her mother out of her wits by staying out all night.

No, there would be some explanation . . . perhaps she’d missed a last tram and been afraid to go home. If Mrs Armstrong’s determination to see her son through university was anything to go by, she was a strong-willed woman.

She’d had an interesting conversation with Stanley about their respective mothers only the day before, sitting close together on the secluded bench by the duck pond.

‘It’s a wicked thing to say, but there are times when I’m ashamed and embarrassed by my mother,’ she’d said.

She could still recall Stanley’s understanding nod.

‘It’s a perfectly normal part of your growth development, Dorothy. Don’t you see? There’s often an element of hate in the relationship between a mother and a daughter. Ruby’s going through that phase at the moment with our mum. It’s a striving for independence, a growing desire to sever the umbilical chord.’

Dorothy unbuttoned her navy-blue serge skirt and stepped out of it. Surely the word hate was a bit much when used in connection with one’s mother? It was just that her mother was so . . . so insular-minded. Her horizons were set no further than her own ornately iron-wrought front gate. She wasn’t interested in the least about what was going on in Europe, or at the Disarmament Conference, or in the fact that a man called Hitler, a man who loathed the Jews, had recently become the German chancellor. Phyllis didn’t want to talk about it. All she wanted to talk about was Margaret’s engagement to Gerald Tomlin from London, and the approaching date of the wedding.

‘What we need in this country is a leader with fire in his belly,’ Dorothy had told her, quoting Stanley, and Phyllis had said. ‘Fire in his stomach, dear. Belly isn’t a nice word for a young girl to use.’

‘Thy belly is like an heap of wheat set about with lilies. Thy two breasts are like two young roses that are twins,’ Dorothy had replied, just to be difficult. ‘You’ll be saying that the Song of Solomon isn’t nice next.’

‘Parts of it are extremely vulgar,’ Phyllis had retorted, unabashed.

One thing was certain, Dorothy told herself as she started to roll down her black woollen stockings, her sister Margaret would never want to sever the umbilical chord. It was as if she had obediently fallen in love with Gerald Tomlin just to please her mother. Because, as a continuation of the good little girl she had always been, she could be happy only if her parents were happy.

Muttering to herself as she rummaged in the untidiness of her dressing-table drawer for a pair of lisle stockings, Dorothy asked herself how any girl of twenty-one, as pretty as Margaret, could be smitten with a man in his middle thirties with sandy hair, freckles, and wet lips? Personally she found him utterly repulsive with his charm laid on with a trowel, and his yellow spotted cravats, not to mention the hideous Max Baer pouched sports jackets he chose to wear.

To love a man like that . . . ugh! It was enough to make one feel sick, she told herself, turning round and checking that the seams of her stockings were straight. Then she wondered vaguely whether to tell her father about the lecture they’d had that day at school about careers in the Civil Service. The prospect of going to work in the mill office appalled her, even though the draughty little building was situated down a long flagged slope, well away from the deafening clatter of the looms in the weaving shed.

Which brought her thoughts back full circle to Ruby Armstrong. No wonder she’d run way. What chance had she had to improve her station by learning shorthand and typing privately? What chance of anything with a brother as brilliantly clever as Stanley, and with a mother who washed other people’s clothes all day so that her son could stay on at school and pass one exam after another?

Dorothy opened her wardrobe door and took out her favourite dress of the moment, blue crêpe with white spots and a white floppy organdie bow at the neckline.

It was certainly funny that Ruby hadn’t taken any of her clothes with her, but then she’d probably had this wild romantic notion of walking out of the house into the arms of her lover – because surely there was a lover somewhere? – with nothing but the clothes she stood up in. It was like a story out of a magazine. Like the beginning of a serial in one of the Woman Pictorials Mrs Wilkinson brought to the house.

Leaving everything behind, everything she had held most dear, she walked away to a fresh beginning, anew life with the man who loved her from the depths of his very soul. . . .

‘Are you there, Dorothy?’ Margaret Bolton put her head round the door then came in and walked straight over to the mirror.

‘Just look at my hair,’ she said without preamble. ‘Gerald’s coming to dinner, and I haven’t time to wash it and get it dry. It’s been one hell of a day at the office. Mr Martin gave me four letters to type at the last minute, then he made me do one over again. He might be the Education Officer, but he’s hopeless at putting words together.’ She held out a strand of her fair hair. ‘Do you think if I wet the ends with sugared water and put a few curlers in, it would curl up in time?’

‘It looks all right to me,’ Dorothy said, easing her feet into black court shoes without glancing in her sister’s direction. ‘Anyway, when you marry your Gerald, he’ll have to see you looking a mess sometimes. Will you be sleeping in curlers like you do now, with Ponds cold cream on your face?’

‘Of course not. I’ll wait until he’s gone to the mill, then I’ll put my curlers in underneath a turban.’

Margaret was answering quite seriously, having thought this out only the week before. ‘Gerald doesn’t even like me putting my lipstick on or powdering my nose in front of him. He likes his women to look as if they make no effort at all to look pretty.’

‘His women?’ Dorothy raised an eyebrow.

‘A joke,’ Margaret, who never made them, said. Then leaning closer to the mirror she pulled at her half-fringe, tram-lines of anxiety furrowing her broad forehead. ‘I wish you’d try to be nicer to Gerald, our Dorothy. He’s not all that happy at the moment having to stay with Auntie Ethel and Uncle Raymond until the wedding. Uncle Raymond is always talking about what it was like in the trenches in Flanders Fields all those years ago, and Beryl stares at him.’

‘Stares at him? Whatever for?’

‘Gerald thinks it’s because she has a crush on him. She does it when they’re having a meal, and he says he can’t chew his food properly because every time he looks up from his plate, there she is. Staring at him.’

‘Well, at least he can’t accuse me of that,’ Dorothy said, running a comb through her thick curly hair and being glad it curled naturally and didn’t have to be helped along with hot water with sugar melted into it.

‘Stanley Armstrong’s sister’s missing,’ she said all at once.

Margaret turned round from the mirror looking so much like her mother that Dorothy flinched.

‘You mean that boy out of Inkerman Street? His sister?’

‘You know very well who I mean. You must have heard Mother telling me how I’m lowering myself being friendly with a boy like that.’

‘There’s no need to get so uppity for heaven’s sake.’

Dorothy jerked at the narrow belt on her frock. ‘She’s for ever reminding me how lovely the boys at the tennis club are, and urging me to join the Young Conservatives. And why I have to learn shorthand and typing privately when I could leave school in July and go to the Technical College in September, I don’t know. Is there some virtue in paying for education? I have to mingle with the scholarship girls at school after all.’

‘You’ve got Bols

hie ideas, our Dorothy. And I knew something was wrong when I telephoned Gerald at the mill. He sounded quite upset and he said the police were there. Something to do with one of the girl weavers, he said.’

Dorothy tweaked the organdie bow into position, and leaning round her sister at the dressing-table, outlined her lips with purple lipstick then wiped it off again.

So Stanley had been right. They were treating it as foul play. Mrs Armstrong must have convinced the police that her daughter would never have stayed out all night without letting her know. She felt the gloom of unease settle around her as if someone had suddenly draped a damp blanket over her shoulders. She wanted for some inexplicable reason to take her feelings out on Margaret who was watching her now with a martyred expression on her face. The shorthand lesson loomed ahead in her mind like the promise of some medieval torture, and she wanted her sister to retaliate to her mood by shouting at her, or at least by walking out of the room and slamming the door. There were times when she could hear herself being nasty, and the feeling was strangely exhilarating.

‘A demonstration of one’s baser feelings is common,’ her mother had told her once. ‘Anyone would think you were a mill girl at times, Dorothy. In clogs and shawl.’

Dorothy hadn’t bothered to remind her mother that the girls at her father’s mill never wore clogs and shawls; that it was Grandma Lipton, Phyllis’s mother, who had gone to work dressed like that, being knocked up by a man called Daft Jack who walked the early morning streets, rattling on the windows of the terraced houses with a stick with umbrella spokes on the end of it. To mention this would have tightened Phyllis’s mouth into a grim line, and frozen her neat features into a mask of distaste.

It was for this reason that Grandma Lipton had never been brought from the Nursing Home to be there when Gerald Tomlin was visiting.

‘She does it on purpose,’ Phyllis had said. ‘She’s proud of the way we’ve got on in one way, and yet in another she resents it.’

The Clogger s Child

The Clogger s Child Gemini Girls

Gemini Girls Polly Pilgrim

Polly Pilgrim Emma Sparrow

Emma Sparrow A Better World than This

A Better World than This The Listening Silence

The Listening Silence Maggie Craig

Maggie Craig Since He Went Away

Since He Went Away Lisa Logan

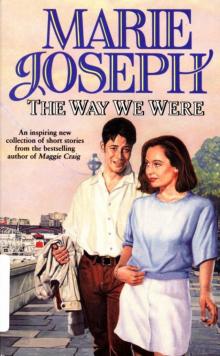

Lisa Logan The Way We Were

The Way We Were The Travelling Man

The Travelling Man Footsteps in the Park

Footsteps in the Park