- Home

- Marie Joseph

Footsteps in the Park Page 9

Footsteps in the Park Read online

Page 9

‘Well?’ the three pairs of eyes queried.

‘I don’t suppose you stayed more than a minute,’ Phyllis said, giving her the cue.

Dorothy shook her head. ‘There’s to be a post-mortem this afternoon,’ she told them reluctantly. ‘At two o’clock.’

Ethel nodded with satisfaction. ‘To see if she was interfered with; there’s some men should have it chopped off and that’s a fact.’

Phyllis’s thick eyelids lowered themselves like defensive shutters. ‘Why don’t you and Beryl go upstairs, dear? You can show her the drawings Margaret made for the head-dresses, and see what she thinks.’ She drew a circle in the air with her forefinger. ‘It’s a round wreath, Ethel. Tiny rosebuds, we thought, and I’ve booked the three girls in for early appointments at Pierre’s. You wouldn’t consider having Beryl’s hair permed? Say, just the ends?’

Firmly Ethel shook her head. ‘It takes the nature out,’ she said, ‘all that baking. It stands to reason.’

Phyllis sighed. ‘Ah well. I’m having mine done the day before of course. I’ll be far too busy to go into town on the morning. If I pin it well and keep my net on it should be quite all right.’

‘Your mother only sent us upstairs so that you wouldn’t say anything else about the murder,’ Beryl said, sitting down gingerly on the edge of Dorothy’s bed. ‘I think it’s awful the way everybody’s going on about it. I’m not going to ask you anything about it, so don’t think I am. I saw Stanley Armstrong the other day when I was coming out of school. He was running down West Road, and he looked awful.’

‘I didn’t know you knew him?’

‘I’ve seen you together lots of times, coming out of the side park gates. But you never saw me.’ Her glance was sly, and Dorothy turned away to hide the hated blush.

‘Gosh, I do wish I’d been born a boy,’ Beryl went on. ‘It was awful in the night. I was rolling about in bed with pain. Mother says she’d take me to a specialist in Manchester if she wasn’t sure I’d grow out of it. I can never be in the netball team or anything because if it comes on the day I’d be there sitting on a deck-chair in the cloakroom with a hot-water bottle on my stomach and Miss Haydock giving me hot water with Indian brandy in it.’

‘Is that what you have to do when you’re ill? Sit on a deck-chair in the cloakroom?’

‘There’s nowhere else.’ Beryl rubbed hard at her stomach. ‘Yes, I do wish I’d been a boy.’

Dorothy sat down on the padded stool at her dressing-table, and privately agreed that life would have been easier for Cousin Beryl if she had been a boy. An only child, she would, if she’d been a he, have gone straight into her father’s timber business, needing neither Matriculation nor Higher School Certificate, nor indeed any of the social graces Auntie Ethel seemed determined to drum into Beryl. Music lessons, elocution, extra coaching in French, and dresses made by Ethel’s own dressmaker, a Miss Randle, whose idea of chic was to have enough material left over for a matching belt and a push-back beret style hat. She looked in the mirror and saw her cousin’s reflection. She really did look rotten. The round face had a greenish tinge to it, and as she drooped forward, her greasy hair fell over her face, not quite concealing two angry red spots on her chin.

‘What sort of a mood was Gerald in when he brought you home just now?’ she asked unexpectedly.

Dorothy pulled a face at herself in the mirror. ‘Oh, oozing charm as usual. He told me his life story, wanting me to feel sorry for him for some reason. Why do you ask?’

Beryl jerked her head upwards, presenting a suffering face to the ceiling. ‘Because he was really snotty at breakfast, that’s why. I thought perhaps he and Margaret had had a lovers’ tiff. They went to the pictures last night, didn’t they?’

‘How did you know that?’

‘Because I asked him where he was going, that’s why. Usually he just says “out” when I ask him. Mother says I shouldn’t ask him so many questions, but I worked it out when he first came to stay with us that it would be the only way of getting him to talk to me. He ignores me. I could be a stick of furniture for all he knows or cares, he certainly doesn’t use his charm on me. That’s because I’m not pretty like you, and I’m not, so you don’t need to say I am. Oh, I do wish I’d been a boy, ’cos looks wouldn’t have mattered then. I mean to say, look at your Stanley. Nobody could say he’s good-looking, now could they? He’s too thin for one thing, and pale. Not like Gerald. He’s got lovely colour, hasn’t he? Do you know who I think he’d be the spit image of if he had dark hair? Ronald Colman. His voice is exactly the same . . . Gosh, fancy being married to someone like that! Your Margaret doesn’t know how lucky she is.’

What was it Margaret had said? Dorothy shook her head sadly as she remembered: ‘Beryl stares at him when he’s eating. And follows him about asking him personal questions. If we weren’t getting married soon Gerald says he’d have to find somewhere else to stay. She’s driving him bonkers.’

Oh poor Cousin Beryl. It had been the same for as long as Dorothy could remember. Always in love with someone; for ever nursing an unrequited passion for the most unlikely people. The biology mistress. Taking little posies of flowers to school and leaving them with anonymous little notes on her desk. That tall boy in the choir, the golden-haired one who snuffed out the candles before the sermon with the air of knowing how beautiful he looked doing it. Before his voice had broken Beryl had gone to every service on Sundays, sitting where she could feast her eyes on him, and once drawing his profile in the flyleaf of her hymn book. Once, a long time ago, she had put her arm round Dorothy’s waist and said, ‘Let’s be best friends for ever, you and me, and tell each other everything, shall we?’

With a feeling akin to shame Dorothy remembered the way she had stiffened and moved away, muttering that she didn’t want to be best friends with anyone, that best friends weren’t her line at all. She looked at the bowed figure, the drooping head, and with a flash of intuition realized that this was the way it would always be for Beryl. Always swooning with love for someone unattainable. Perhaps deliberately unattainable . . . The issues were too complex for her to unravel at the moment; her mind was still reeling with the shock of seeing Stanley and his mother trapped in their inconsolable grief. In more normal times she would have discussed it with Stanley in the way they sometimes would spend hours discussing other people’s idiosyncrasies.

‘You’d think there was only thee and me normal,’ he had said once after they had spent a satisfactory half-hour analysing her mother’s motivations. Yes, Stanley would have had a very satisfactory theory about Beryl. . . .

And now she had fixed on Gerald. Driving him mad with questions; watching him, prying, just so he would have to talk to her.

‘He hasn’t gone out in the evenings as much lately,’ Beryl was saying gloomily. ‘Before he got engaged to Margaret he used to go out almost every night in his car.’ She fingered one of the spots on her chin sadly. ‘When I asked him where he was going, he laughed and said he just liked driving alone. Fast, in the dark all on his own. Out as far as the moors. It made me think of Heathcliff wandering alone over the moors looking for someone to love.’

‘Heathcliff?’ Dorothy’s reaction was more disparaging than she had intended it to be. ‘I can’t think of anyone less like Heathcliff than Gerald Tomlin. For one thing Heathcliff didn’t drive over the moors in a red MG sports car. He strode.’

‘I’m glad he’s found happiness at last. He’s got such a lovely accent.’

‘He talks like an ha’penny book,’ Dorothy said, getting up from the stool. ‘Let’s have a look at the sketches, shall we? I’ve had just about enough of Gerald for one morning.’

‘I simply love weddings, don’t you?’ Beryl trailed along the landing, walking carefully. ‘Gosh, wouldn’t it be awful if Margaret had her you know what on her wedding day? Won’t it be beady if they have a baby straight away?’

Eight

‘YOU CAN TALK about inquests and post mortems till the cows come h

ome,’ Ada Armstrong said, her face set in stubborn lines of disbelief. ‘But if our Ruby had been expecting I’d have known.’ She glanced at Stanley, then away and at Mrs Crawley. ‘Tha’s only a lad and not supposed to know about such things, but you can’t live in a house like this with the only privacy being if tha goes out and bolts theself in the outside lavatory. And anyway, our Ruby weren’t that sort of girl. If she’d thought she was like that and her not wed she’d have been half out of her mind. She couldn’t have kept a thing like that from me.’

Mrs Crawley’s face, beneath the inevitable halo of daytime curlers, was soft with compassion. No gleam of fascinated interest, Stanley noted, no shocked surprise even, certainly no wait-till-I-tell-the-neighbours attitude. Just honest-to-goodness sympathy, and a desire to help.

‘They said she was almost three months gone,’ Stanley said, turning to Nellie Crawley. ‘So if it was the same man who killed her – and they’re sure it must have been now there’s a motive, so to speak – that would mean she was meeting him around Christmas time.’ He turned back to his mother. ‘Mum, we’ve got to think. What did she do about Christmas time? Did she go to any parties? I know some of the girls from the mill had parties . . .’

‘She weren’t like that,’ Ada said, shaking her head as if she would shake the words away. ‘I would stake my life that Ruby weren’t like that. She was a good girl . . . a good girl.’

‘It’s the good ones what get caught,’ Mrs Crawley said. ‘The poor little sod. She must have been well nigh out of her mind, keeping that to herself.’ She shook a finger at Ada. ‘And it’s not the worst sin now, Mrs Armstrong, not by a long chalk. I’ve always thought that. There’s bloodymindedness, and coldness, and meanness, and lust. Aye, lust, Mrs Armstrong. And I’ll swear by our Holy Mother that your Ruby weren’t guilty of none of them.’ She jerked her head in the direction of the scullery and winked at Stanley. ‘Put the kettle on, there’s a good lad, and you sit you down, Mrs Armstrong. You’ve had more than you can take, and that’s a bloody fact.’

Ada looked at her piteously. ‘How could I not know? What’s been happening in this house, for the love of God? Me only daughter meeting some man on the sly all these past weeks, and having his baby, and I didn’t suspect? What sort of a mother have I been? Why couldn’t I see there was something sadly wrong with her?’ She looked for a confirmation that could not be given. ‘How long did she think she could keep it from me? I’d have tried to understand. Even if she wouldn’t tell me who it was – and he was a married man, I’m more convinced of it than ever now – I would have stood by her.’

‘Of course you would, love.’ Mrs Crawley was guiding her gently towards the rocking chair. ‘You’re not the sort of mother to throw her daughter out on the streets because she makes a slip. You’d have looked after her and then you’d have brought up the baby yourself while she went back to work.’ The curlers glistened in a sudden shaft of sunlight as she got carried away. ‘You’d have put him in yon basket where them shirts are, you would, and if any of the neighbours ‘ad said anything, you’d have spit in their eye.’ She patted Ada’s arm. ‘And I’d have spit in t’other one for you, love, that I would.’

‘It was an older man,’ Ada said, picking up her pressing cloth from the table and twisting it round and round in her hands as she talked. ‘I’ve thought so all along, and I’m saying it again. Ruby went out with Eddie next door for a good twelve-month, and I’ll swear there was nothing going on. She had her head screwed on all right, and she’d have known how to handle Eddie Marsden if he’d started anything.’ The piece of fent tore down the middle and she flung it from her. ‘So it must have been an older man, one with a smooth tongue, a persuasive sort of man who could undo in one minute all that I’ve been telling her since she grew up. “Never sell yourself cheap” I used to tell her. “If a man wants to marry you enough, he’ll wait.”’

‘Not like my bugger,’ Mrs Crawley said, lowering her voice in the vain hope that Stanley out in the scullery wouldn’t hear. ‘I were four-month gone when we got wed, then just two weeks to the day after the wedding I lost it. And that were it.’ She gave her cackle of a laugh. ‘Maybe it were all that jumping down steps and sitting in a tin bath swiggin’ gin what did it. Any road I never had another chance.’ She winked at Ada. ‘And it weren’t for t’want of trying, not in them early days it weren’t.’

It was no use deciding not to listen. Not a bit of use closing the scullery door that was never closed anyway. Mrs Crawley’s voice carried like a clarion call. She was talking about the funeral now.

‘How much did you have on ’er, love?’

‘Nothing. Harry didn’t believe in insurance.’

‘Well, I’ve never heard nowt like that before. I’ve had twopence on me husband and threepence on me mother-in-law for years. If she doesn’t die quick I’ll have bought all t’bloody cemetery.’

Stanley waited for the kettle to come to the boil. They seemed to have forgotten that he was there . . . He could feel a sickening sensation churning away in his bowels. He kicked absent-mindedly at the frayed piece of coconut-matting laid over the flagged floor.

Not Ruby. Not his sister, the quiet, gentle, dark-haired girl who had had to go in the mill so that he, Stanley, could study and swot to his heart’s content in a room of his own. Had her pride in his scholastic achievements been more mixed with envy than he had guessed? Had she sought comfort in the arms of some unknown man because the conditions at home had become intolerable to her? Had she resented more bitterly than he could hope to have guessed the fact that she had had to work in some weaving shed whilst he stayed on at school? Had she given herself – he used the phrase without a trace of self-consciousness – to this man with a silver tongue who had promised her an escape and ended up with his hands round her throat, squeezing the life out of her?

The sick feeling in his stomach was growing worse. He opened the back door and took a few deep breaths, then he turned off the gas underneath the kettle, closed the back door softly behind him and went outside. Down the three stone steps, past the meat safe, down the sloping backyard with the low soot-blackened walls separating it from its neighbours, out to the lavatory, where he bolted himself inside.

It was what Mrs Crawley had said. Meant kindly but bringing home to him as nothing else had that Ruby was dead. DEAD. ‘How much did you have on her, love?’ Oh, God, the man from the Prudential knocking at the door on Friday nights, early, before the tea-things were cleared away in the street, catching folks before they went out to spend their wages if they’d been lucky enough to have a week’s work behind them. Twopence on our Edie, threepence on me dad. No wonder his father had thought the whole system barbaric . . . and yet. . . .

Now they would have to plan the funeral, or at least he would have to plan the funeral. There’d be people they hardly knew in shiny black, and his mother leaning on his arm, with the neighbours in the street watching with compassion. With compassion, aye, but watching just the same.

Shut away in the tiny enclosed space, he stared round him at the white-washed walls, the squares of newspaper hanging by a string from a nail, shut away, he scuffed with his feet the tattered rag rug on the flagged floor. Over the outside wall, out in the back he could hear the children from the house three doors up shouting to each other as they came home from school. Old Mrs Preston was calling her cat in, banging on a tin plate, crying its name. The man next door, out of work now for eighteen months, pulled the lavatory chain and shuffled his way back into the house, and streets away the rag-and-bone man called out his unintelligible cry. Life was going on, would go on just the same after Ruby was forgotten. He, Stanley Armstrong, would get up in the mornings and go to work, if he’d been lucky enough to find a job. His mother would wash more shirts, Dorothy would leave school and start as a typist in her father’s office, and in a few years’ time she would marry a young fellow who was a director in his father’s firm. They’d have the reception at The Pied Bull over on the edge of the moors

, and their photographs would be in the weekly paper, laughing into each other’s eyes, with a description of the bridesmaids’ dresses underneath. And all this would be a million years away.

And if you’d asked him, he couldn’t have told you why he suddenly felt an aching, terrible despair, so that the sobs tore at his throat with a rasping noise that made him stuff his fist into his mouth. He knew that he was crying for his sister, for what seemed to be the death, too, of all his hopes, but there was more. There was something else his tormented brain was weeping for. His ideals, his unexpressed emotions about love and tenderness. And lust. Mrs Crawley had been right to use that word. He, Stanley Armstrong, had lusted after Dorothy Bolton. He’d dreamed of her, but in his dreams his love for her had been no more than a stroking of her yellow hair, a holding her close, a kissing of her eyelids.

The tears ran down over his hand and he groaned aloud. But that wasn’t love. Not the reality of love. Love was Mrs Crawley sitting in a tin bath and drinking gin, and love was Ruby lying on the grass with the weight of some unknown man above her. And love was Ruby dead with a leaf caught up in her hair.

Mrs Crawley’s voice could be heard calling out from the open back door.

‘Are you all right, love? Your mum wants to know. Are you all right out there?’

But he made he reply, just stayed there with the agony of disillusionment growing inside him as if it were a living thing.

Nine

‘WHERE WAS HE ringing from, dear? I shouldn’t think Mrs Armstrong is on the telephone, is she?’

Phyllis’s voice breathed a tolerance she was obviously far from feeling. It had been a most trying day again, with Dorothy mooning round the house with a cold that didn’t seem all that much in evidence, and Mrs Wilkinson going on and on asking questions.

The Clogger s Child

The Clogger s Child Gemini Girls

Gemini Girls Polly Pilgrim

Polly Pilgrim Emma Sparrow

Emma Sparrow A Better World than This

A Better World than This The Listening Silence

The Listening Silence Maggie Craig

Maggie Craig Since He Went Away

Since He Went Away Lisa Logan

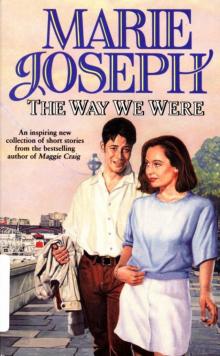

Lisa Logan The Way We Were

The Way We Were The Travelling Man

The Travelling Man Footsteps in the Park

Footsteps in the Park